Of Bats and Men: A Conversation with Poet and Writer Sage Marshall

In his new poetry anthology 'Echolocation,' Sage Marshall meditates on boyhood, hockey practice, learning to hunt, and other places where pain and beauty collide.

Author: Katie Hill

When I first became aware of Sage Marshall, I considered him a bit of an adversary. Maybe he thought of me that way, too.

He worked for Field & Stream as a full-time news editor while I was writing news for MeatEater, and then Outdoor Life. We jockeyed for space in the outdoors headlines, covering many of the same poaching cases, record-busting critters, conservation issues, and viral videos of wildlife eating each other. For all intents and purposes, if the internet was the Everglades and pageviews were prey, he was a Burmese python and I was an alligator.

This dynamic hasn’t changed much. We still cover news for our respective titles, both as freelancers now. If we’re anything like normal journalists covering normal beats (yawn), the lurking competition of one creates pressure and a ticking clock for the other. Except now, the only difference is that Marshall and I have spent many cumulative hours talking. I consider him a friend and a role model in chasing creative dreams.

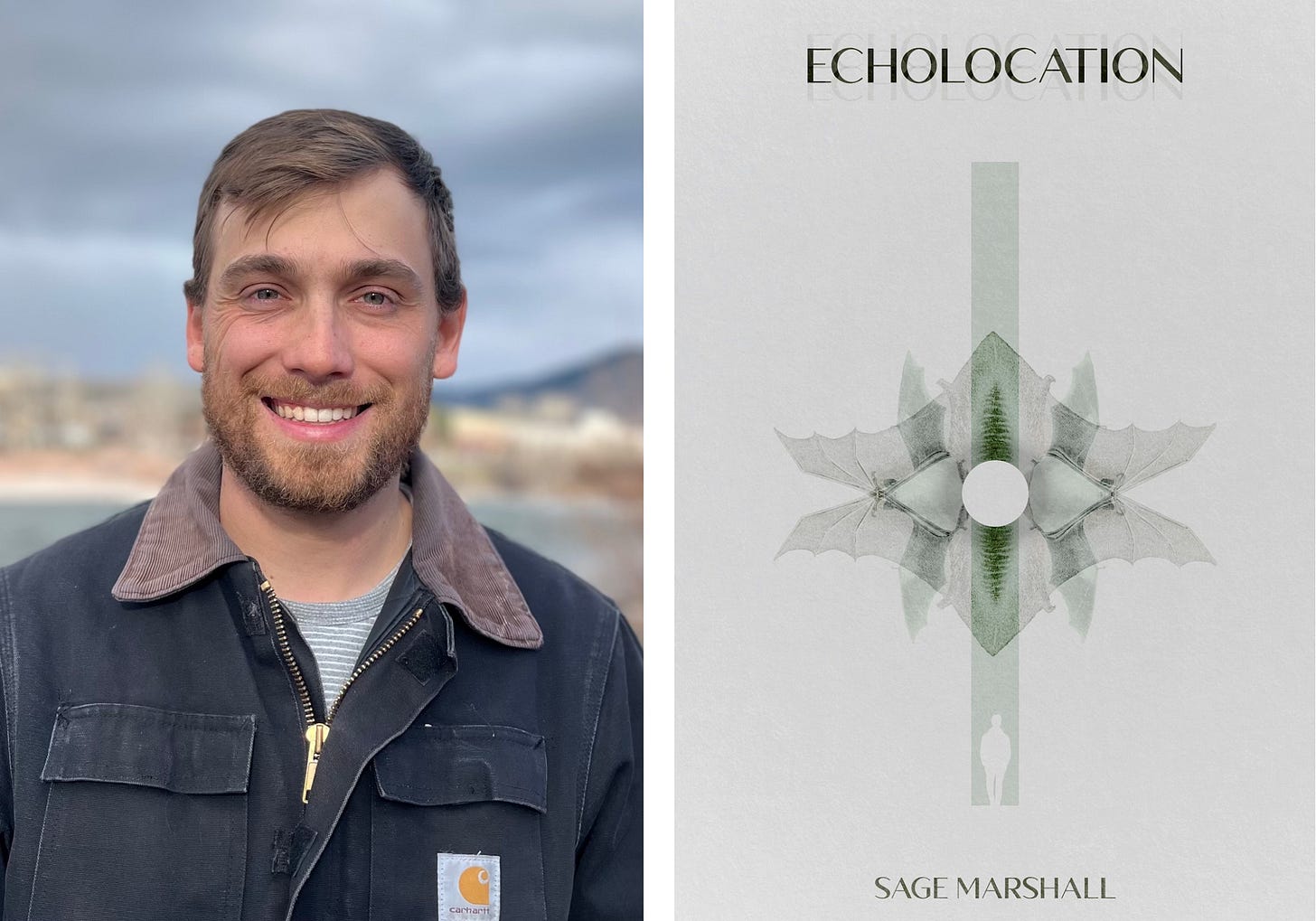

For those faces of our relationship, I’m lucky. My luck expanded when I got the chance to peruse Marshall’s debut poetry anthology, “Echolocation” (Middle Creek Publishing, 2024), which published on Oct. 1. (Buy the 52-poem collection here.)

Marshall works and writes from Missoula, Montana, where he lives with his partner Bela and their rescue Wirehaired Pointing Griffon, Gunney. The couple moved to Missoula from northern California in June 2023, although Marshall is originally from Telluride, Colorado. Shortly after moving, Marshall enrolled in the creative writing MFA program at the University of Montana, a storied degree established by poet Richard Hugo whose notable alumni include James Welch, Amanda Eyre Ward, and Steven Rinella.

In “Echolocation,” Marshall fixes his gaze on what reads as an Americana upbringing, blending the harsher parts (family fights, nausea at hockey practice, putting a boarding school frenemy in a headlock) with the joyous ones (catching nightcrawlers, rooftop swigs of Jameson, campfires). By stripping whatever protective lacquer glazes boys when they become men, he reveals a core that — despite years of conditioning to tolerate blood, cheap tobacco products, and other bycatch of adolescence — still bruises quite easily.

That same vulnerable core tends to ache when we kill deer, birds, and other game animals. Marshall reminds us of this with multiple hunting and fishing scenes interspersed throughout the more nostalgic entries. It hurts the same in adulthood when a trout swallows a fly as it did in childhood when we pierced spasming worms with barbed Eagle Claw snells. Marshall is proof of something easily lost in modern outdoor media: writing about hunting and fishing is just as artful and human-centric as writing about less messy subjects.

Ultimately, from a collection laced with death emerges a vaster, brighter understanding of life and its many beautiful corners. Ever relatable, Marshall is right there with all of us, fumbling around in the dark at top speed — trying to make it out unscathed and failing brilliantly.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

KH: Talk about the journey that led to this collection. I’ll leave it up to you to determine how deep you want to go with that.

SM: Most of these poems I wrote between 2020 and 2021. At the time, I was moving around different parts of the U.S. First I was back in Colorado, then I went back to California. I was trying to figure out where I could call home and who I was as an adult. These poems were a part of that process. Oftentimes, I was reflecting on the land and the people around me.

One of the themes I gravitated toward was boyhood and the beauty there, and the violence as well. A lot of these poems focus on the years when I was growing up. That ranges from things like playing ice hockey or football or mountain biking, how the boys I grew up with and I found ways to care for each other, and how we often hurt ourselves and each other in the process.

KH: I love that. You allude to bats a lot. It evokes this image of collision, bats colliding with each other in the dark in an attempt to find their way. This whole collection feels very full of collisions, between humans and other humans, between humans and animals. How have your collisions shaped you?

SM: This collection has a lot of poems that reflect on either physical or emotional scars that are part of the pain of life. But from that pain, a lot of the poems find places of beauty and understanding — or some kind of relief — through the natural world. I wouldn’t say that’s in spite of the collisions, but I would say the collisions are part of creating that contrast. There’s a negative element, but it’s certainly not all negative. For example, I do reflect on the hard times I’ve had with my dad and brother. I composed that first poem, “Echolocation,” in my head, in 2020, right at the height of COVID-19 lockdown. The three of us went on a backpacking trip in Coyote Gulch in Utah. That trip was the impetus for that poem, which is one of the warmer, fuzzier ones of the collection.

KH: You use place, landscape, and natural beauty as a salve for some of the sharper, harsher emotions of strained interpersonal relationships, or even the more physically painful collisions of hunting and hockey practice. Place is a soothing element here. You talk about alpenglow a lot. Even just that word is very calming.

SM: Mm-hmm. I hope I don’t use it too much. (Laughter.)

KH: No, quite the opposite! There’s a lot of contrast. You talk a lot about fire, blood, heat, sharpness, the blazing sun, anger. Then you also talk a lot about water, ice, denim, darkness, some sadness, and alpenglow, which I picture being sort of blue. Do you feel like these contrasts build some tension?

SM: I think so. Contrasts and contradictions are at the heart of what seems to make these poems work together. One of the reasons alpenglow is such a fun poetic concept is because it describes the way light hits mountains and how a mountain can look different depending on that light. In the early morning, before the sun rises, the granite might look like a soft blue. Then it goes through the harshness of direct sunlight during the day, and once the light gets soft again in the evening, it becomes more of a gentle red.

The job of a poet is to put light on different topics from different angles. Maybe that sounds kind of mushy, but it’s actually pretty special. I try to write poems that could be interpreted in a straightforward way, but they also have room for deeper interpretation. And when it comes to those deeper interpretations, I might know less than the reader.

KH: That’s very humble of you to say.

SM: I mean, I think it’s true. Do you think writers are the best interpreters of their work? Or do you think other people are?

KH: I guess you put work out into the world and you hope people meet it where it’s at and then carry it forward into their own lives. Then, it percolates in those spaces that remain foreign to you as the writer.

SM: Yeah, I like that way of thinking about it.

KH: I know you’re working on a memoir, and obviously you’re a journalist. Why poetry? Why is this a medium you gravitate toward?

SM: I never really thought poetry was something I could do at a high level, because it always felt so intangible to me. I’ll write a poem and have no idea if it’s good or not, and the majority of the time it’s not. That speaks to the mysterious aspect of poetry. It’s the most mysterious form of writing in my opinion. I don’t know how poems work or don’t work.

I was always a super avid reader, and I wrote poems when I was really little. Then I went away from poetry as I got deeper into hockey. I came back to it when I went back to undergrad [at Wesleyan University] after playing juniors. I took a couple of short poetry classes with some master poets that came to the university. Those poets really encouraged me. They saw something in my work and gave me a lot of faith. I was studying with Marie Howe early in undergrad. She is an incredible poet, and she came up to me after a workshop and said it was an honor to read some of my work. That meant a lot. She probably wouldn’t remember it now, but it gave me the faith that I might actually be able to do this.

I also really like being able to write stuff without having to explain it. A lot of poets create work that explains itself more than mine does. But, I like being able to write something, be a little bit vague, and still have it resonate. I’ve always been fascinated by the different sounds of words and language. Poetry is a way to draw that out intensely. If you’re trying to [write prose] really sonically, you might get frustrated.

KH: Does anything bring up anxiety in writing poetry?

I do worry about writing poems that aren’t going to stand up to the test of time. When I was trying to figure out which poems to include in the collection, I read them really hard and tried to think about what I’d think of them five years from now. Obviously this is the collection of a young poet, and it talks about a lot of themes of adolescence and early adulthood. Ultimately, I will continue to mature as a writer and poet and person, and some of this stuff will probably feel immature years from now.

KH: Do you have a few standout poems within the collection that you’re partial to? Or is that like picking favorite children?

SM: I really like the first two [“Echolocation” and “The Springs”]. I wrote them early on, and I think they provide a launching point into the broader collection. I like the hunting scenes, too. I mostly like the feel-good poems. The other poems might be better, but they’re also harder for me to look at.

KH: Do you feel comfortable talking about what it was like writing about your family? In instances where we are frustrated with our families, maybe we have a tendency to keep those cards close to our chest. We don’t always broadcast that we’re having a hard time with loved ones. How did it feel putting some of these more personal emotions and exchanges, or your interpretations of them, out into the world?

SM: It was definitely hard, especially because most of the people I write about — my family members in particular — are people I’m really close with. I hope I wrote about them in a way that shows there’s still love there, despite those struggles. We’re taught not to speak poorly about our family, out of respect. I don’t always buy that. I think there’s power in being able to write, talk, or be open about those challenges. Maybe not everyone agrees with me, though.

One of the hardest parts of writing about family is that they don’t really get to respond. Their record of events might be different from mine, which might be hard for them. So I try to be cognizant of that. One way I justify writing about the hard stuff with my family is by trying to be critical of myself as well. I try my best not to let myself off the hook.

KH: Keep a little balance in the universe.

SM: Yeah, I’m certainly not that kind of person, and I would hope I don’t come across that way.

KH: So has your family read all of these poems?

SM: No.

KH: Are you excited for them to read them? Or will that be an exercise in expressing that individuality and still maintaining love underneath?

SM: I’ve written about the challenging aspects of those relationships before. We have a pretty open dialogue about this stuff. When I write a poem, I try to think about what will best serve it. Not every poem in here is total and complete nonfiction. Some of the characters and dialogue get changed here and there. I would say to my family, not all of this is about you. A lot of these poems have lives of their own.

“I try to write poems that could be interpreted in a straightforward way, but that also have room for deeper interpretation. And when it comes to those deeper interpretations, I might know less than the reader.”

KH: Let’s talk about how hunting and fishing fit into “Echolocation.” You get the sense that you’re looking at a montage of an American boy’s life, and hunting and fishing certainly nestle into that blueprint here. Is this collection, by some definition, hunting and fishing poetry? Or is it more than that? Obviously, there are plenty of poems in here that are not about the outdoors, but they share themes with the ones that are.

SM: It would be accurate to say that, in some sense, this is a hunting and fishing poetry collection. I wrote most of this while I was working full-time at Field & Stream, and during that time I was also learning how to hunt. I first went hunting in 2021 so it was something I was new to, and it was making a big impression on me.

I find hunting very poetic. Very few things in life have such strong themes of life and death or ways to reckon with your choice to express violence in such an explicit and literary way.

As far as the poems about fishing go, my relationship with my dad revolved around fishing from an early age. I would choose to put fishing in every collection I ever write, if given the option.

KH: You riff on a line from Kurt Vonnegut’s “Slaughterhouse Five.” “Everything was beautiful and nothing hurt.” You change one word in that phrase to turn it into “Everything was beautiful and everything hurt.” Talk about this.

SM: Vonnegut’s epitaph is satire. And I took good satire, made it non-satirical, and called it poetry. (Laughter.) But this poem encapsulates the heart of the work of this collection, which is to take the things that hurt and draw out the beauty that’s still there. I have a hard time seeing how something is beautiful if there’s not also the potential for pain or anguish. When something is important, there’s hurt no matter what.

KH: If you ask many hunters, inflicting pain and death on an animal is the least desirable part of hunting, and yet something beautiful comes of it. Do you think there’s some truth to that?

SM: I think so. That pain and that beauty live pretty close together. It means that you’re living and feeling. You’re not numb, and you’re open to the world. Oftentimes, just being open to the world means you’re going to hurt in certain ways. And when we pay attention to that, we can find beauty.

There are moments in this collection where I write about accidentally killing a fish while fly fishing, and that wouldn’t have happened if I weren’t intentionally trying to hook the fish and reel it in. You’re choosing to inflict pain on other creatures.

When I was learning how to hunt, I felt really nervous about killing. That aspect of hunting was super scary to me. I write about my first deer hunt in this collection. I got into a few places where I could have taken shots and I didn’t. I was pretty terrified of crippling an animal, and causing pain without resolving it. But yeah, what do you think it is about hunting that makes you choose to inflict pain, and it’s still beautiful?

KH: Well, usually there’s some lingering semblance of beauty in the place. You could be in a treestand over a clearcut or a corn feeder, and there’s still beauty there. The animals themselves are beautiful. The whole taxidermy industry revolves around creating beauty out of death.

But there’s something painful inherent in the realization that we are capable of killing. You sum it up really well in the last lines of “Hunting Scene 1.”

We do not know / where the pain goes / but how to make it.

We like to hold ourselves in high regard, but especially for those of us who started hunting after our frontal lobes were fully formed, we had already established positive views of ourselves. And then one morning we woke up and loaded a rifle with multiple bullets and we shot them at an animal and we killed that animal. Not only did we do it on purpose, but we woke up at 4 o’clock in the morning, we wore special clothes, we lurked around in the dark, we sat still for a really long time, and we rode out the elements in order to kill that animal.

That’s pretty antithetical to the way that I think of myself outside of the hunting context. I don’t think of myself as someone who would go through a lot of effort to inflict pain. But we interact with a lot of beauty on the way to that inflection point, and then in the moments immediately after, there’s beauty too.

I feel all of that in your hunting poems very astutely. In “Hunting Scene 2,” you end with:

It astounds me / the violence I inflict / & in it the world rends such beauty.

SM: I wrote that poem after going on my first duck hunt in California with my friend and mentor Amanda. Before I learned how to duck hunt, I had no idea that all these ducks existed. I just knew the mallard. It sounds very silly to say that now. But during that hunt, I shot an amazing pintail, and I was stunned by the beauty of this duck that I would never see in a town pond. They live out in the wild, and they’re insanely beautiful.

That’s what I was reflecting on. If I had not started hunting, I honestly believe I would never have known what a Northern pintail was. I would have never held one up close and gotten to see the color of its head.

KH: Yeah, that proximity is so unique. And then in “Hunting Scene 3,” you jab your hand on a cactus, and you’re crawling after a mule deer.

In the sage sea I watch / hand still on the trigger / dripping with blood.

There’s some crazy irony and symbolism. Your hand is literally bleeding as you’re in the process of trying to pull the trigger.

There’s just a lot of really good stuff in here, Sage. Talk about some of your other inspirations. You have a decent number of instances in here where you’re writing based off of X poet or Y author.

SM: I would certainly say that the poets whose work I respond to here are folks I’ve been inspired by. I’ve been inspired by writers like Jim Harrison and Denis Johnson. In terms of poetry, Louise Glück’s work has endlessly fascinated me with its intertwined philosophical and emotional concerns.

My biggest poetry mentor, whom I worked with a lot in undergrad, is John Murillo. He writes more about Blackness and Black masculinity, but his approach to poetry really inspired me. Years ago, when I was an undergrad, he talked about duende, which refers to writing with heart, writing that has heat in it. He certainly does that in his work, and it inspired me to write that way, too. I also get a lot of inspiration from poets Youssef Komunyakaa and Jim Jordan.

KH: Yeah, you certainly write with a lot of heat. I love this poem that references Glück, “As If a Dream.” This is a very good example of a poem that feels full of that Americana type of boyhood. You talk about smoking a cherry Swisher Sweet, denim, concrete, gasoline, and sitting by a 7/11 on the curb. I see something very American here. I don’t know why I keep coming back to that.

SM: I like that. I certainly listen to a lot of Americana music. I listen to a lot of Jason Isbell, and I get a lot of inspiration from the ability of musicians to tap into specific emotions or themes that are relatable to other people, especially people who live in the U.S. but aren’t from New York or L.A. I don’t think poetry could ever compete with music, but I hope my poems get kind of close.

I like to write because I don’t always feel like I successfully express myself when I’m speaking, especially when I’m speaking off the cuff. When I’m writing, I can take the time to really say what I’m trying to say.

KH: Yeah, well, that makes two of us. If this is the first interview you’ve given about your poetry, and this is the first time I’ve interviewed anyone about a poetry collection, we’re sort of echolocating at this very moment, if you think about it.

SM: Yeah, totally. (Laughter.)

KH: If you had a line of readers standing in front of you, and you could tell them something about this collection, what would you say? Would you say anything? Or would you just pass it off to them and tell them to go read?

SM: Oh gosh. I’d probably run. (Laughter.) No, I’m kidding. I would talk about how thankful I am to be able to use language in this way to write about my own struggles. Poetry has always helped me get through difficult moments in life. This book is the fruit of that. The idea of someone reading it is exciting and scary and makes me feel insecure, but I’ve already learned so much from being able to play with language and reflect on these things.

In that sense, I think the most important part was writing it. The fun part almost feels done.

“Echolocation” is available for purchase through Middle Creek Publishing. Signed copies are available on Sage Marshall’s website.

Sage Marshall is a poet, essayist, and outdoor journalist. He’s originally from southwest Colorado and currently resides in Western Montana, where he explores the rivers and mountains around Missoula with his partner Bela and their adopted bird dog Gunney. He’s a contributing writer and former editor of Field & Stream. His creative work has been featured in publications such as The Missouri Review, swamp pink, The Appalachian Review, and elsewhere. Follow him on X and Instagram and find more work on his website.

Katie Hill is a freelance outdoor journalist and managing editor of The Westrn. Her writing has appeared in Outdoor Life, High Country News, MeatEater, The Texas Observer, and other publications. For more of her work, check out her website and follow her on social media.