The Narrow Trail Between Predator and Prey

In a landscape of fear, a hunter finds a predator's resolve.

It’s humid for fall in Montana, with heavy clouds overhead, when I park my truck at the end of a long, gravel forest road. Before opening the door, I scan the parking lot scattered with horse trailers, trucks and SUVs for anything out of the ordinary. I’m looking for signs of a potential threat or annoyance.

A few guys sit in an elaborate RV camp. I note that they aren’t out hunting and don’t show any sign of a harvest. Since I have to pass them to get to my trail, I watch to see if they’re getting wasted, taking stock of their faces and body language. My dad taught me to stay away from drunk hunters around the same time I learned to read and ride a bike. The habit has stuck into middle age. Since the campers seem innocuous — and mostly sober — I leave the privacy of my truck, collect my bow, and pack for the evening’s hunt.

When I walk by the camp, the three men seem friendly enough. I want to make sure we won’t be hunting on top of each other, so we run through the usual chitchat. Have you seen any bears? Many other hunters? Besides being courteous, this trailhead gossip provides valuable data for assessing my hunt and general backcountry safety. I want to know who’s around. I want to see their faces. Most of all, I want them to know that I know who they are. Do these people seem helpful in case of an emergency, or do they seem like they might cause an emergency? Or are they neutral?

We talk about hunting this area in past seasons, the bull their brother shot last year, the ridge we like to hunt and how it’s full of downed trees, how much the elk have been calling, and how we usually don’t see grizzly bears here until we’re several miles from the trailhead.

In short, these guys treat me like another hunter, not a curiosity. They register on the positive side of my mental ledger, weighing in favor of the parking lot being safe overnight. They don’t give me any reason to think they are bullies, idiots, rapists, or murderers.

I’m not even a true crime girlie. Rather, I’m a product of growing up in the 90s when it seemed like officials found dead body on the Appalachian Trail every month. But as I start hiking I feel bad that I automatically prepared for the worst from the guys at the trailhead. Sorting people this way is a shame.

But it’s not my shame to bear. Less than a mile up the trail, I’m reminded of why I do it.

While descending the trail, I run into a man hiking up from the stream gully. He’s alone, older, and dressed casually in jeans with no pack. The trail is narrow, steep, and rocky. He blocks my path with his body, shoulders square to me.

Where are you heading? he asks.

Up the trail a bit, I say. I adjust my shoulders to match his.

How far?

As far as I need. I make eye contact with him. I do not hide that I am studying his face.

Looking for a trophy bull?

What a smartass. Only if I’m lucky. I set my jaw and tilt my chin up to open my airway, so my voice deepens.

Are you out here alone?

My husband is meeting me later. (A lie.) I speak with a falling inflection, as a rising inflection at the end of sentences can convey uncertainty.

Are you staying out here tonight?

You’ve got to be kidding me. We’ll see. (Another lie.)

Well, be careful out there. He flashes a toothy sardonic grin.

You too. I match his tone.

The man slowly moves aside, finally. But his eyes follow me. The sky darkens as I walk along the narrow single-track trail, the Douglas fir branches shuddering as a breeze picks up. My evening’s goal is to see if I’m right about the path elk take between their grazing grounds and their daytime bedding area. I’ve heard them bugling from the stream bottom and I’ve bumped them from beds near the ridge. A wide, lush gully between those spots crosses the Forest Service trail I’m hiking. I have a hypothesis that they use this funnel to move up and down the slope.

Tonight I want to test it, to see if I can spot or hear them near it. That will help me plan the next morning’s hunt. I’m going to hike back out to my truck to sleep and walk back in before dawn in the morning. This is somewhat risky because grizzly encounters are more likely during dawn and dusk. I don’t want to surprise a bear on the trail.

But I’m not thinking about any of that now. My shoulders are tightening and my chest cavity is heating up. This is my body saying something is off, and my brain derails to follow it. I work through the feeling’s source as I walk.

What is that man doing out here? He had no pack. Maybe he’s an outfitter checking on something for the next day. But the outfitter camps I know of are miles in — too far to go in on foot without a single piece of gear. Plus, outfitters are typically too task-oriented and self-possessed to be so . . . creepy. Why didn’t I ask him what he was doing? That’s annoying. He seemed overly interested in my itinerary. And not in the way people are when they look out for me, or are just making casual hunting conversation. That’s a red flag. Hunters know to avoid uninvited prying into other hunters' business.

At best, he was being rude and violating social norms. At worst, he could be a predator.

On the trail, my senses hone in on the woods’ patterns. Occasionally, I pause to study the dense vegetation behind me for anything out of place. I’m more alert than fearful. Some would say hypervigilant. The wind is stronger now and my ears tune into every little sound. The treetops rubbing together make mournful noises. I’m used to that strange chorus, but now my ears prick at any whisper.

Is my body cuing into a real risk now, or just a correlation? This feels like a dangerous place I’ve been before. That doesn’t mean I’m in danger right now. I study the ground, looking to the man’s boot tracks for any clues about his activities. Was he actually alone? If not, could someone else still be out here?

I don’t think anyone inclined towards assaulting women targets public land bow season expecting to find them. But I know many human predators are opportunistic. I’m already going to be alert for bears as I hike out in the dark. Do I need to worry about this guy on my backtrail too?

Now I’m thinking and behaving like a prey animal. I’m fixated on sharing the woods with this man. His body language, questioning, and eye contact ruptured my place in the system. Five minutes ago I was a predator, with a predator’s mindset, focused on picking apart my quarry’s routines to better exploit them. I was looking ahead, thinking ahead, and planning my ambush. I love ambush hunting because, when it goes right, it means I solved the equation of elk movement plus landscape rather than just lucking into animals.

But I’m no longer an ambush hunter. Instead, I’m alert for an ambush.

The irony strikes me. I put elk and other animals in this situation all the time. Even when they can’t detect me, they’re still looking for a threat. This is apparent when a lead cow steps out from the treeline at dusk. She takes one step at a time, moving each front hoof with intention. Her neck extends, nose up, sniffing for danger. She’ll stop and look around. She peeks over her shoulder, then another elk appears behind her. Once satisfied she might put her head down and grab a mouthful of forage. But she’ll pop her head up again in just a beat. Slowly, a whole herd populates a meadow this way. I would love to know how often elk have left a place before I even knew they were there. They may not know what exactly was off, but they’d rather never know than die trying to find out.

I wonder how many times that same tendency has saved me from becoming someone’s prey. On walks with my dad as a kid, he taught me to covertly size people up from a distance. Like The Man and The Boy in The Road, we’d hear a truck coming, then melt into the shrubs to observe who was heading down the hill to the railroad tracks. Since we weren’t actually in a Cormac McCarthy story, they were never post-apocalyptic cannibals, just the rangers from the neighboring state park or potential poachers at worst.

This tactic helped me as a teen cyclist when a truck on a country road doubled back one too many times. I used it as an adult in Baja, Mexico one night as a military-style truck overtook my then-husband and me. We had to dump our bicycles loaded with camping gear in a ditch and sprint for cover. I silently thanked hunting for teaching me about concealment as the truck’s spotlight swept over us and the men yelled, “Come out boys!” We remained undetected above them, flattened into a steep hillside of cacti, cholla spines digging into our knees.

People who don’t hunt sometimes question if we’re empathetic towards the animals we kill. Most of us are, and it goes beyond death. I strive to tap into the sensory lives of elk, especially while hunting alone. Being solo quiets my herd instincts, leaving room to account for the elks’ hypervigilance by subtly adjusting my behavior. That often means hunting with less movement and more patience. Sometimes, I feel guilty for accidentally pushing a group of cows. Eating enough to get through winter and then birthing and nursing a calf is energy-intensive work. I come along, bump them by accident, and they waste precious calories. Sorry ladies. I was acting like a creep.

Recalling the many times I’ve protected myself restores my peace on the trail. I have a bow, bear spray, and some dated martial arts training. I also have a heart full of malice for anyone who fucks with me. My caution about the man turns to contempt. He morphs into a creature I’ll be hunting for on my way back out.

If he’s dumb enough to attack someone prepared to take a 700-pound mammal’s life, he’s probably not a very cunning predator to begin with.

I resent him for invading my evening. His bearing in the world momentarily stole my power and direction. I was the actor in my own story. Now I have to worry about being acted upon. To cope, I mentally cast him as an attacker in unsavory action movie scenes. They all end badly for him. My karate instructor always pointed to his head, saying that all good self-defense starts up here. And human predators often don’t pick off victims who seem just as crazy as they are.

Is there any scenario where shooting a human with a compound bow in self-defense makes practical sense? You can’t get me if I get you first.

The catharsis of fantasy violence helps return my attention to reality and the trail. Fewer boot prints disturb the loose, dry singletrack now. As I tune back into the non-human world, I notice a few small elk tracks among the horse hoofprints. I anticipate the smell of elk. This is one of my favorite ways to find them, because scent is so visceral yet underutilized in modern life. Unlike vision, there’s no technology to enhance smell. It’s also the elks’ keenest sense. I prefer to play on equal footing with my quarry. Plus, when I actually do smell them and not their beds, I know I am downwind of them. Catching a whiff of that pungent, slightly acrid, barnyard elk odor awakens something carnivorous in me.

The smell of elk on the hoof seems especially potent when I’m low on meat. Sometimes after many hours of hunting, I fixate on a phrase, worrying it smooth in the background. One of those is hunt hungry. The way my predatory drive fluctuates with my freezer’s fullness is folk wisdom grounded in the literal gut truth. Predators tend to operate better on an empty stomach. Falconers who painstakingly weigh their birds before releasing them for a hunt know this. Even my overfed housecat is unmotivated by a fake bird on a stick.

Hunting with a nose to the breeze like a furry four-legged feels as fundamentally human as digging in the soil or stoking a campfire. It’s also absurd since I only moonlight as a predator. Really, I’m a bumbling Wile E. Coyote following a cartoon scent cloud, haplessly trying to outwit full-time prey.

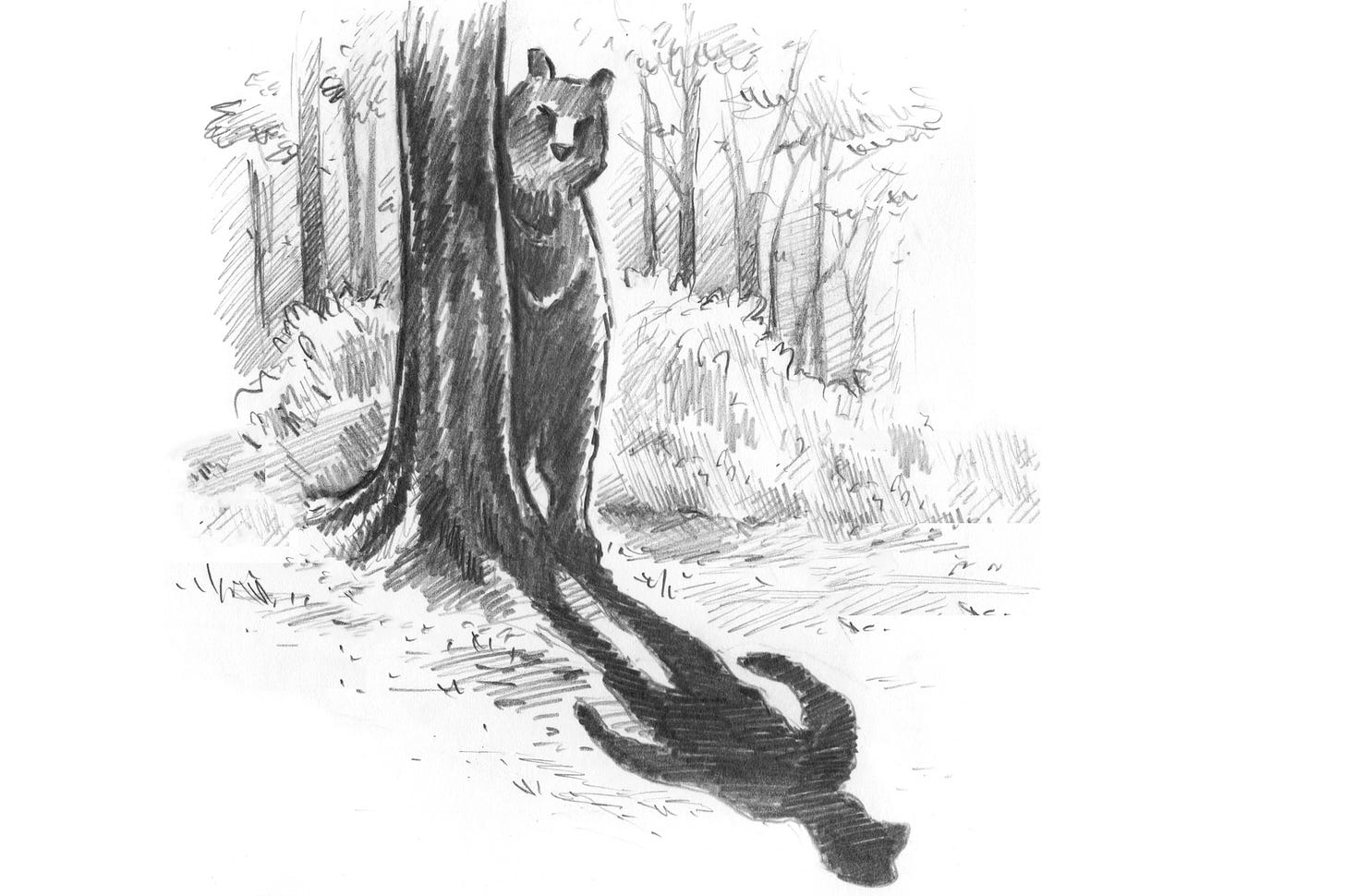

That elky smell never wafts across the trail. Chalk it up to swirly wind. Perhaps they sniffed me out first. Soon, I see a fresh and clearly outlined bear track in the dust, pointing up the trail. I crouch down to see the characteristic straight-across toe pattern of a grizzly, not the arcing toe pattern of a black bear. It’s very large.

It was nice being on top of the food chain for a moment.

Now, I’m not exactly at risk of being preyed upon by a grizzly bear. They are omnivores that would rather be left alone to eat roots, bugs, and delicious scavenged elk. My problem is that bowhunters intentionally do all of the wrong things in bear country. We sneak around quietly in low light conditions, potentially near elk carcasses. Similar to how I fantasized about making that strange man my victim instead of becoming his, grizzly bear logic dictates that neutralizing me would be the safest option.

While most of my backcountry grizzly encounters have been thrilling yet uneventful sightings, I’ve had a couple of close calls. The most frightening moment happened as my hunting partner and I bugled back and forth with some bull elk on a hillside. My considerably taller friend noticed a grizzly with a cub in tow heading up-slope and parallel to us, about 100 yards away. She seemed unaware of us, minding her own business just as we minded ours. As we stood to leave — deliberating if we should make extra noise — I turned around to see her barreling down the slope towards us with her youngster kicking up dust behind.

My friend and I planted our feet into the slope and readied our bear sprays in case she charged within range. We calmly and sternly yelled, “Hey bear!” We agreed to spray if she broke through the shrubs about 10 yards in front of us.

She turned around right at the shrub line. Then she rounded on us again. This time, I had a sinking feeling that our bear spray wouldn’t stop her. We stayed firm and calm with our canisters in front of us. Once again, she stopped at the shrubs, then turned uphill with her cub. My friend and I hurried without running in the opposite direction, taking turns looking over our shoulders and mouthing holy shit at each other over and over.

Later, an outfitter told us about the elk carcass nearby. The sow likely caught our scents when she crossed above us on the way to the carcass, and perceived us as threats to her food and cub. With those strikes against us, I’m surprised she didn’t maul at least one of us. There’s no way to know, but had I been alone that day — instead of standing next to a much bigger man — that sow probably would have shredded me. Every foray into grizzly habitat involves risk assessment, and no amount of training or savvy makes up for the safety of numbers.

I’m going to have to be extra alert if I keep going up the trail.

It’s at this point that I realize that I’ve gone from being prey, to predator, and back to prey again in a few short hours. We evolved to hunt and avoid being hunted. Flipping the sensory switch between those states, or embodying them at the same time, is another way to come closer to the authentic human condition. This is one reason I accept the calculated risk of hunting grizzly country.

Even as I savor how these predator and prey mentalities vie for psychic control, I’m aggravated at how men are interlopers within that dynamic. At 16, I volunteered for a field ecologist in Virginia. As we clipped leaf samples in a ginkgo grove, he mentioned that he might start carrying a pistol for his fieldwork in Alaska, in case of brown bears. He reflected on the unique fear of losing his place as a top predator. From my step ladder under the yellow canopy, I said it sounds like the way I feel running on the Appalachian Trail. This was a revelation to him. Even then, I noted that a brilliant, middle-aged ecological geneticist had never considered the reality of being a teenage girl.

Doug Peacock talks about the importance of sharing the backcountry with grizzlies for putting humans in our place. Bears could kill and eat us but they usually don’t, he says. I appreciate the ecological purity of that, the romanticism of it. I’ve long held that in my heart alongside what my teenage nervous system already knew about feeling like prey.

In the 1990s, Yellowstone National Park’s wolf reintroduction inspired scientists to coin the term ‘ecology of fear’ or ‘landscape of fear’. The idea is that the impacts predators have on prey behavior cascade through the food chain from wolves, to elk, to the aspens and willows elk eat. Put simply, if elk fear wolves, they don’t eat as many trees. Since then, research on the ecology of fear tells a more complex story. But the phrase remains evocative.

‘Landscape of fear’ pops into my head when I’m hunting areas where elk have changed their behavior in the face of intense human pursuit. Or when the same truck drives past my camp too many times, pushing me to move spots. In this case, the predator-prey cascade links the strange man in the truck, me, and the elk I didn’t hunt that day.

Scientists once thought fear had only fleeting impacts on the nervous and hormonal systems of wild animals. Elk, small mammals, and songbirds evolved as prey, so they don’t experience what we call trauma, the hypothesis went. We’re now learning that vigilance can have PTSD-like effects in wildlife too, rippling through prey populations, sometimes even suppressing their reproductive potential.

If we mapped our society’s landscape of fear I’m positive we’d be appalled at the toll taken by hypervigilance, at the collective potential wasted by time spent looking over shoulders instead of boldly ahead.

A few minutes after the bear tracks, I finish calculating the risk of continuing on. It’s already going to be dark when I get back to camp. And there’s still the bugaboo of that guy I saw earlier. I decide I’m ready for dinner and bed. The elk can wait until morning. Shooting an elk by myself in the evening when I know there is a grizzly bear in the area would be risky.

On the hike out I cautiously put one foot in front of another. The analytical, highly-evolved part of my brain knows I won’t likely run into a bear that night. I focus on all the people who hunt alone in grizzly country every year, take greater risks, and aren’t mauled.

My lizard brain and nervous system argue otherwise. My heart and respiratory rates increase along with intrusive, graphic thoughts. Shadows from my headlamp take on mammalian outlines that make me jumpy. I play a mental slideshow of photos from hunters who survived grizzly maulings but almost had their faces ripped off. I imagine what it would feel like to have my scalp turned into a skin flap, or hear a tooth crunch into my skull as I curl into a ball on the ground. I question if my pack is large enough to protect my vital organs while in the fetal position. With my bear spray already in my hand just in case, I’ve imagined my way into an adults-only haunted-house level reactivity.

As I do every season, I think about escaping a mauling, and the possibility of wildlife managers culling a federally threatened animal just because I wanted to bumble around in the dark and fail at hunting elk. What little thought I give the man from earlier goes to imagining that anyone stepping out of the night and into my headlamp beam will likely get a face full of bear spray before they have the chance to say boo. I question if hunting in this spot alone is worth the stress.

“There’s nothing to fear in the dark that you can’t see in the daylight.” When Dad said that to me as a kid he was talking about walking to the wood pile in the yard, not this.

When I finally hear the creek and see the trailhead sign, I relax. Then, I notice a headlamp beam near my truck and groan internally at a new person. I’m not in the mood to move if they’re bad company. Before I can take stock, a man’s friendly voice says hello. I check my bear mace at my belt and grudgingly head over.

He’s a Floridian on sabbatical from his soul-sucking career. Throughout his bow season, he’s started an impressive number of days at 3 a.m. to hike up mountains in the dark. I compare my last few nerve-jolting hours to his happy-go-lucky attitude with some envy and some judgment. He did, at least, have the sense to leave his last spot because a grizzly came into his backcountry camp.

He is thinking about getting a pistol for bears and wants to know if I carry one. I don’t, I tell him. I have bear spray for bears. Sometimes I carry a .243. But that’s just for people. I pause and make eye contact for dramatic effect.

He chuckles nervously, and it thrills me a little to put him on his heels. For a second I’m the predator again. But the cost is that we are no longer the same, are no longer commiserating prey animals. Since he seems kind and glad for company, I want to restore balance to our two-person ecosystem. I explain my strange interaction with the man I encountered hiking in and how it set me on edge all evening. He’s sorry I have to worry about people in a way he doesn’t. We discuss the merits of various tools and tactics for avoiding grizzly conflict. I tell him about the guy who accidentally shot his hunting buddy during a mauling. We eat our dinners at his tailgate, split a beer, and swap a few more stories.

Is this what it’s like to be a dude? You meet other hunters and bullshit with each other? You can just be yourself and don’t have to risk-assess every individual on the fly?

Back at my truck, I crawl into bed as rain plinks the camper shell. I have to make a plan for the morning and decide if I should return to the same spot. Being wedged between a man and a grizzly on the trail drained me.

A hypothetical version of that scenario is now part of the cultural conversation about women’s experiences. Would you rather be alone in the woods with a strange man or a bear? Most choose the bear.

I’ll continue to resist this question because I’ve been choosing both for years. Instead, my choice lives between maintaining a predator’s mindset or giving in to a world that wants me to be prey. I can’t predict exactly how other people and wild animals will behave. But I’ll prepare the best I can. So, I arm myself behaviorally and literally against men, and I walk through bear country with respectful preparation. I’d rather be a player on the landscape of fear than watch from the outside.

The next morning my calls attract a silent bull out of the stream bottom to within 40 yards of my hiding place. I draw my bow, but never gain a clear shot. As I slowly let down my draw, the elk sees the movement. He turns to walk away.

Kestrel Keller is Executive Editor of The Westrn. Their writing and reporting on science, conservation and rural culture has appeared in High Country News, Smithsonian, National Geographic, MeatEater, Outdoor Life, Outside, and many others. Kestrel is a reverse transplant from Bozeman, Montana to Upstate New York.

Gripping!

Nice piece. I have missed your writing.